VENICE, THE ISLAND CITY

A Trip Around the World with DWIGHT L. ELMENDORF, Lecturer and Traveler.

“The Pearl of the Adriatic,” she has been called. “Queen of the Sea” is another of the poetic terms applied to her. If all the expressions that have been used by admirers to pay tribute to the beauty of Venice were gathered together, they would make a glossary of eulogy of considerable size. It was inevitable from the beginning that Venice should receive such homage; for she has a beauty that distinguishes her from all other cities. She is absolutely unique in picturesque attraction and in romantic interest. There are many cities that draw the admiration of the traveler: there is but one Venice, and anyone who has been there and felt her spell cannot wonder at the worshipful admiration that she has received from the time of her birth in the sea.

The fascination of Venice for the traveler is such that ordinary terms of appreciation are insufficient. The city takes complete possession of one, and visitors who have surrendered to her charms are referred to as having the “Venice fever.” All who love beauty have had more or less violent attacks—the artist is most susceptible to it.

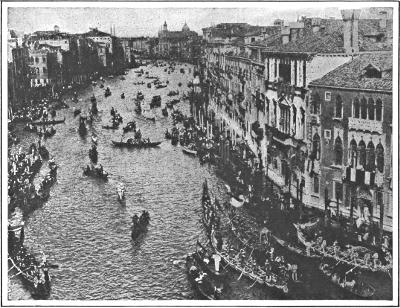

THE GRAND CANAL DURING A FÊTE

This is the main artery of traffic in Venice. It is nearly two miles long, and varies from 100 to 200 feet in width. It is adorned with about two hundred magnificent old patrician palaces.

Low power very large scale integration prototype for three-dimensional discrete wavelet transform processor with medical application

We present a low-power 3-D discrete wavelet transform processor for medical applications. The main focus is the compression of medical resonance image (MRI) data, although the system could be used as a generic compression chip. The architecture eliminates redundant filter banks by using a central control unit to dynamically adjust filter parameters. An on-chip cache is used to process block inputs minimizing result throughput. Power consumption has been kept to a minimum by placing constraints throughout the entire design process. The modular processor has been prototyped using 0.6-μm complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) (three metal) technology. It has been simulated at the functional, circuit, and physical levels. The performance measures of the prototype, area, time delay, power, and utilization have been evaluated. The prototype operates at an estimated frequency of 272 MHz and dissipates 0.5 W of power.

Wael Badawy, Michael Talley, Guoqing Zhang, Michael Weeks, and Magdy Bayoumi, “Low Power Very Large Scale Integration Prototype for Three-Dimensional Discrete Wavelet Transform Processor with Medical Applications,” The SPIE Journal on Electronic Imaging, Vol. 12, Issue 2, April 2003, pp. 270 – 277.

Your broken promises speak about you, but they do not hurt me

Now a day, we meet, we talk, I offer, you promise, and I listen.

Then, I wait, wait and wait, AND you do not perform or deliver.

You do not show up again because you got busy and forgot.

So, I will not go back and review your promises; I will move on.

Your promises were valuable for me, because I believed you care,

And now, I know that I am not on your mind any more.

Your broken promises speak about you.

Your broken promises speak about your commitments.

Your broken promises say “you are interested but not committed”.

But, I am committed and not interested,

So, I have to focus on only committed but not interested,

But I promise that once I am interested, ….

…. I will call you to share our interests with no commitment.

The way you do anything is the way you do everything…

And, I am committed and you are just interested, So,

…. we can not have a business together.

T

Estimating the Cost of Civil Litigation !!

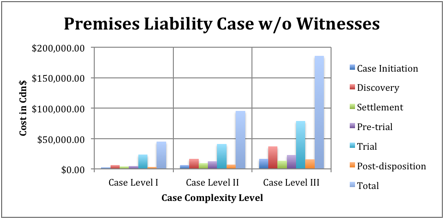

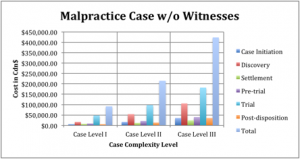

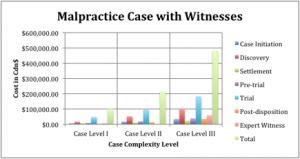

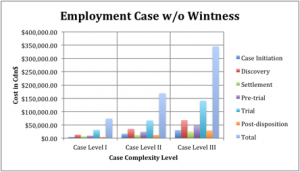

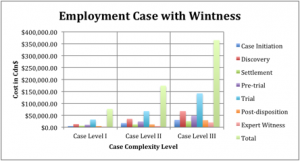

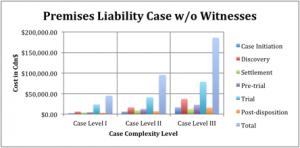

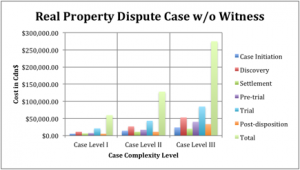

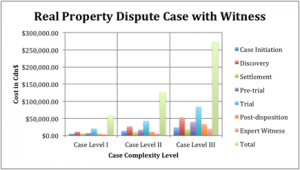

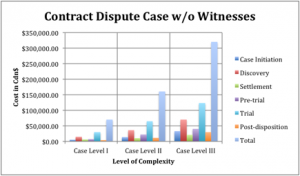

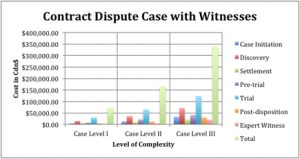

THE National Center for State Courts (NCSC) developed a model of cost estimation that is based on the time of expended by attorneys in various litigation tasks in a variety of civil cases filed in state courts. The litigation cycles are presented in another blog.

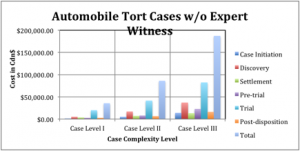

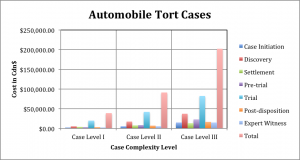

The NCSC published an estimation of numbers of hour in to be used in different cases. The model has three types of cases from complexity level and it assumes there are a senior attorney, junior attorney and a paralegal involved in each case. The model has six types of litigations and the time expended by attorneys is to resolve a “typical” automobile tort, premises liability, professional malpractice, breach of contract, employment dispute, and real property dispute.

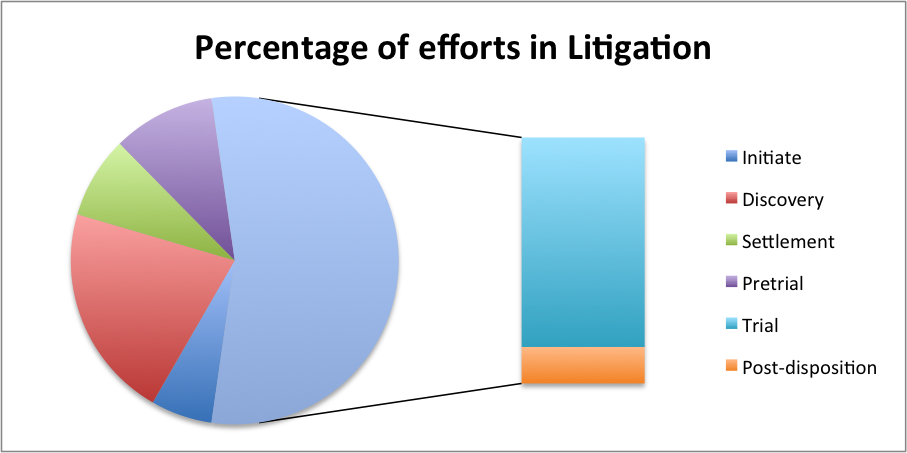

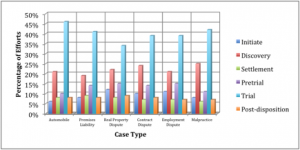

The model uses three levels of complexity of case. The projected effort for each level is estimated based on a survey of different attorney officer. The medians of the percentage of efforts are shown in Figure 1, where each case type is split into six different litigation stages. The litigation stages will vary from a case to another based on the type of the case.

The model also deals with the witness as a separate parameter. The Model did not consider the cost of production of material, cost of communication, copying or duplication, binging, transcript productions, cost of undertaking, cost of service and Court fees. The typical number of discovery does not include cost of cross-examination. In my evaluation the cost will increase by about 150% on the average if we add cross-examination, and the other costs. The Court fees are very minimal compare other cost.

To understand the cross-examination cost. For each hour of cross-examination, two hours of preparation is required on the average and about $350 to produce the transcript. A typical 2 days of cross examination which will cost about 6 days of legal fee in addition to about $5600 to produce the transcript and the other cost involved with the reporters. The cost of undertaking, examining the undertaking and exchange letters to the other party. The Cost of printing or duplication will be about $1 per page and the cost of binding is premium. The Cost of sending or receiving faxes is about $2 per page. The cost of reading emails or phone is in 6 minutes increments. Note that the cost of sending 10 emails 1 line each to a lawyer will cost 1 hr to read and 1 hr to reply as lawyers will charge 6 minutes per email read and reply.

Figure 2 – Figure 13 show the different project cost of different cases and the cost can reach hundreds of thousands of dollars only in legal cost.

Figure 1 The median of effort in six litigation automobile tort, premises liability, professional malpractice, breach of contract, employment dispute, and real property dispute.

Figure 1 The median of effort in six litigation automobile tort, premises liability, professional malpractice, breach of contract, employment dispute, and real property dispute.

Figure 2 The projected Cost of cases of automobile tort without an expert witness. The cases are modeled as three different levels of complexity.

Figure 2 The projected Cost of cases of automobile tort without an expert witness. The cases are modeled as three different levels of complexity.

Figure 3 The projected Cost of cases of automobile tort with an expert witness. The cases are modeled as three different levels of complexity.

Figure 3 The projected Cost of cases of automobile tort with an expert witness. The cases are modeled as three different levels of complexity.

Figure 4 The projected Cost of cases of Malpractice without an expert witness. The cases are modeled as three different levels of complexity.

Figure 5 The projected Cost of cases of Malpractice with an expert witness. The cases are modeled as three different levels of complexity.

Figure 6 The projected Cost of cases of Employment dispute without an expert witness. The cases are modeled as three different levels of complexity.

Figure 7 The projected Cost of cases of Employment dispute with an expert witness. The cases are modeled as three different levels of complexity.

Figure 8 The projected Cost of cases of premises liability without an expert witness. The cases are modeled as three different levels of complexity.

Figure 9 The projected Cost of cases of premises liability with an expert witness. The cases are modeled as three different levels of complexity.

Figure 10 The projected Cost of cases of Real Property without an expert witness. The cases are modeled as three different levels of complexity.

Figure 11 The projected Cost of cases of Real Property with an expert witness. The cases are modeled as three different levels of complexity.

Figure 12 The projected Cost of cases of Contract Dispute without an expert witness. The cases are modeled as three different levels of complexity.

Figure 13 The projected Cost of cases of Contract Dispute with an expert witness. The cases are modeled as three different levels of complexity.

Figure 13 The projected Cost of cases of Contract Dispute with an expert witness. The cases are modeled as three different levels of complexity.

Disclaimer :

This post is for informational purposes only and does not provide legal advice. Materials on this website are published by Wael Badawy and to provide visitors with free information regarding the laws and policies described. However, this website is not designed for the purpose of providing legal advice to individuals. Visitors should not rely upon information on this website as a substitute for personal legal advice. While we make every effort to provide accurate website information, laws can change and inaccuracies happen despite our best efforts. If you have an individual legal problem, you should seek legal advice from an attorney in your own province/state.

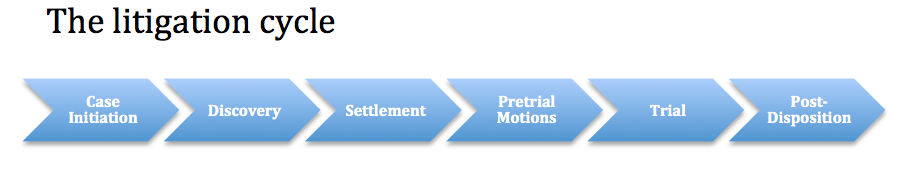

The litigation cycle.

As the litigation can be very complex or very simple is can be modelled to six stages. The stages are Case Initiation, Discovery, Settlement, Pretrial Motions, Trial, Post-Disposition.

For all case types, a trial is the single most time-intensive stage of litigation, encompassing between one-third and one-half of total litigation time in cases that progress all the way through trial. Discovery is the second most time-intensive stage, encompassing between one-fifth and one-quarter of total attorney hours. The remaining litigation stages each required less than 15 percent of total attorney time.

The settlement can happen any stage. An appeal will start as well in stage 1, Discovery may not be as deep as the original cycle.

Activities within each stage is detailed below.

Stage 1: Case initiation

Initial fact investigation; legal research; draft complaint/answer, cross-claim, counterclaim or third-party claim; motion to dismiss on procedural grounds; defenses to procedural motions; meet and confer regarding case scheduling and discovery.

Stage2: Discovery

Draft and file mandatory disclosures; draft/answer interrogatories; respond to requests for production of documents; identify and consult with experts; review expert reports; identify and interview non-expert witnesses; depose opponent’s witnesses; prepare for and attend opponent’s depositions; resolve electronically stored information issues; review discovery/case assessment; resolve discovery disputes.

Stage 3: Settlement

Attend mandatory ADR; settlement negotiations; settlement conferences; draft settlement agreement; draft and file motion to dismiss.

Stage 4: Pre-trial Motions/Applications

Legal research; draft motions in limine; draft motions for summary judgment; answer opponent’s motions; prepare for motion hearings; argue motions.

Stage 5: Trial

Legal research; prepare witnesses and experts; meet with co-counsel (trial team); prepare for voir dire; motion to sequester; prepare opening and closing statements; prepare for direct (and cross) examination; prepare jury instructions; propose findings of fact and conclusions of law; propose orders; conduct trial.

Stage 6: Post-Disposition

Conduct post-disposition settlement negotiations; draft motions for rehearing, JNOV, additur, remittitur, enforce judgment; any appeal activity.

—-

Disclaimer :

This post is for informational purposes only and does not provide legal advice. Materials on this website are published by Wael Badawy and to provide visitors with free information regarding the laws and policies described. However, this website is not designed for the purpose of providing legal advice to individuals. Visitors should not rely upon information on this website as a substitute for personal legal advice. While we make every effort to provide accurate website information, laws can change and inaccuracies happen despite our best efforts. If you have an individual legal problem, you should seek legal advice from an attorney in your own province/state.

A Low Power Architecture for HASM Motion Tracking

This paper proposes low power VLSI architecture for motion tracking that can be used in online video applications such as in MPEG and VRML. The proposed architecture uses a hierarchical adaptive structured mesh (HASM) concept that generates a content-based video representation. The developed architecture shows the significant reducing of power consumption that is inherited in the HASM concept. The proposed architecture consists of two units: a motion estimation and motion compensation units.

The motion estimation (ME) architecture generates a progressive mesh code that represents a mesh topology and its motion vectors. ME reduces the power consumption since it (1) implements a successive splitting strategy to generate the mesh topology. The successive split allows the pipelined implementation of the processing elements. (2) It approximates the mesh nodes motion vector by using the three step search algorithm. (3) and it uses parallel units that reduce the power consumption at a fixed throughput.

The motion compensation (MC) architecture processes a reference frame, mesh nodes and motion vectors to predict a video frame using affine transformation to warp the texture with different mesh patches. The MC reduces the power consumption since it uses (1) a multiplication-free algorithm for affine transformation. (2) It uses parallel threads in which each thread implements a pipelined chain of scalable affine units to compute the affine transformation of each patch.

The architecture has been prototyped using top-down low-power design methodology. The performance of the architecture has been analyzed in terms of video construction quality, power and delay.

A Low Power Architecture for HASM Motion Tracking

|

Wael Badawy and Magdy Bayoumi, “A Low Power VLSI Architecture for Mesh-based Video Motion Tracking,” The Journal of VLSI Signal Processing-Systems, Kluwer Academic Publishers, invited.

To access my blog, you should register for free

Hi

To access my blog, please register in my site for free

or

visit https://www.badawy.ca and select register from the menu.

Thank you

Wael

A Low Power VLSI Architecture for Mesh-based Video Motion Tracking

This paper proposes a low-power very large-scale integration (VLSI) architecture for motion tracking. It uses a hierarchical adaptive structured mesh that generates a content-based video representation. The proposed mesh is a coarse-to-fine hierarchical two-dimensional mesh that is formed by recursive triangulation of the initial coarse mesh geometry. The structured mesh offers a significant reduction in the number of bits that describe the mesh topology. The motion of the mesh nodes represents the deformation of the video object. The architecture consists of motion estimation and motion compensation units. The motion estimation architecture generates a progressive mesh code and the motion vectors of the mesh nodes. It reduces the power consumption, uses a simpler approach for mesh construction, approximates the mesh nodes motion vector by using the three step search algorithm and uses a parallel motion estimation core to evaluate the mesh nodes motion vectors. Moreover, it maximizes the lifetime of the internal buffers. The motion compensation architecture uses a multiplication-free algorithm for affine transformation, which significantly reduces the complexity of the motion compensation architecture. Moreover, using pipelined affine units contributes to the power savings. The video motion compensation architecture processes a reference frame, mesh nodes and motion vectors to predict a video frame. It implements parallel threads in which each thread implements a pipelined chain of scalable affine units. This motion compensation algorithm allows the use of one simple warping unit to map a hierarchical structure. The affine unit warps the texture of a patch at any level of hierarchical mesh independently. The processor uses a memory serialization unit, which interfaces the memory to the parallel units. The architecture has been prototyped using top-down low-power design methodology. The performance analysis shows that this processor can be used in online object-based video applications such as in MPEG and VRML.

Published in:

Circuits and Systems II: Analog and Digital Signal Processing, IEEE Transactions on (Volume:49 , Issue: 7 )

- Page(s):

- 488 – 504

- ISSN :

- 1057-7130

- INSPEC Accession Number:

- 7460367

- DOI:

- 10.1109/TCSII.2002.805248

- Date of Publication :

- Jul 2002

- Date of Current Version :

- 10 December 2002

- Issue Date :

- Jul 2002

- Sponsored by :

- IEEE Circuits and Systems Society

- Publisher:

- IEEE

Wael Badawy and Magdy Bayoumi, “A Low Power VLSI Architecture for Mesh-based Video Motion Tracking,” The IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II, Vol. 49, July 2002, pp. 488-504.