MRI Data Compression Using a 3-D Discrete Wavelet transform

A low-power system that can be used to compress MRI data and for other medical applications is described. The system uses a low power 3-D DWT processor based on a centralized control unit architecture. The simulation results show the efficiency of the wavelet processor. The prototype processor consumes 0.5 W with total delay of 91.65 ns. The processor operates at a maximum frequency of 272 MHz. The prototype processor uses 16-bit adder, 16-bit Booth multiplier, and 1 kB cache with a maximum of 64-bit data bandwidth. Lower power has been achieved by using low-power building blocks and the minimal number of computational units with high throughput.

Published in:

Engineering in Medicine and Biology Magazine, IEEE (Volume:21 , Issue: 4 )

- Page(s):

- 95 – 103

- ISSN :

- 0739-5175

- INSPEC Accession Number:

- 7389345

- DOI:

- 10.1109/MEMB.2002.1032646

- Date of Publication :

- Jul/Aug 2002

- Date of Current Version :

- 07 November 2002

- Issue Date :

- Jul/Aug 2002

- Sponsored by :

- IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society

- Publisher:

- IEEE

Wael Badawy, Guoqing Zhang, Mike Talley, Michael Weeks and Magdy Bayoumi, “MRI Data Compression Using a 3-D Discrete Wavelet transform,” The IEEE Engineering in Medical and Biology Magazine, Vol. 21, Issue 4, July/August 2002, pp. 95-103.

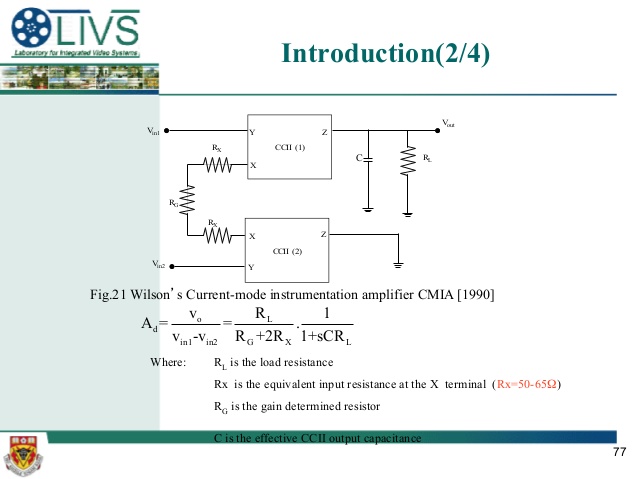

A Novel Current-Mode Instrumentation Amplifier Based on Operational Floating Current Conveyor,

This paper presents a novel current-mode instrumentation amplifier (CMIA) that utilizes an operational floating current conveyor (OFCC) as a basic building block. The OFCC, as a current-mode device, shows flexible properties with respect to other current- or voltage-mode circuits. The advantages of the proposed CMIA are threefold. First, it offers a higher differential gain and a bandwidth that is independent of gain, unlike a traditional voltage-mode instrumentation amplifier. Second, it maintains a high common-mode rejection ratio (CMRR) without requiring matched resistors, and finally, the proposed CMIA circuit offers a significant improvement in accuracy compared to other current-mode instrumentation amplifiers based on the current conveyor. The proposed CMIA has been analyzed, simulated, and experimentally tested. The experimental results verify that the proposed CMIA outperforms existing CMIAs in terms of the number of basic building blocks used, differential gain, and CMRR.

Published in:

Instrumentation and Measurement, IEEE Transactions on (Volume:54 , Issue: 5 )

- Page(s):

- 1941 – 1949

- ISSN :

- 0018-9456

- INSPEC Accession Number:

- 8601828

- DOI:

- 10.1109/TIM.2005.854254

- Date of Publication :

- Oct. 2005

- Date of Current Version :

- 03 October 2005

- Issue Date :

- Oct. 2005

- Sponsored by :

- IEEE Instrumentation and Measurement Society

- Publisher:

- IEEE

Yehya H. Ghallab, and Wael Badawy, Karan V.I.S. Kaler and Brent J. Maundy, “A Novel Current-Mode Instrumentation Amplifier Based on Operational Floating Current Conveyor,” IEEE Transaction on Instrumentation and Measurement, Volume 4, October 2005, pp. 1941 – 1949.

Obiter.

By George Neilson.

THE claims of the legal profession to culture were cleverly belittled by Burns, when he made the New Brig of Ayr wax sarcastic over the town councillors of the burgh:—

“Men wha grew wise priggin owre hops an’ raisins,

Or gathered lib’ral views in Bonds and Seisins.”

Bonds and seisins are certainly not the happiest intellectual feeding ground. “I assure you,” said John Riddell, a great peerage antiquary, “that to spend one’s time in seeking for a name or a date in a bit of crabbed old writing does not improve the reasoning powers.” Riddell was a keen critic of Cosmo Innes, who subsequently had the happiness of passing the comment upon Riddell’s observation that “perhaps it is not in reasoning that Mr. Riddell excels.” Yet the annals of the law shew many splendid examples of the union of close textual study of manuscript, with an enlarged outlook on first principles and with keen critical insight. Perhaps Madox was a more permanently serviceable scholar than Selden. One can see from Coke’s margins, his infinite superiority to Bacon in exact knowledge at first hand of older English law. But when all is said, we could have done much better without Coke and Madox than without Bacon or Selden. It is delightful to be able to appeal to Chaucer for perhaps the most emphatic compliment to law, in respect to its capacity for literature, that it has ever received. Amongst all the Canterbury pilgrims, there was no weightier personage than the Man of Law:—

“Nowher so bisy a man as he ther nas,

And yet he semed bisier than he was.

In termes hadde he caas and domes alle

That from the tyme of King William were falle,

Therto he coude endyte and make a thing

Ther could no wight pinche at his wryting,

And every statut coude he pleyn by rote.”

Yet it was this learned and successful counsel, alone of the party, who knew the poet’s works through and through, and had the list of them at his finger-ends. Good Master Chaucer for this touch we offer hearty thanks! Was it in Herrick’s mind when he penned his fine tribute to Selden?

“I, who have favoured many, come to be

Graced, now at last, or glorified by thee.”

Wits and poets have had many hard things to say in jest and in earnest about the legal profession and its work. Herrick bracketed law and lawyers with diseases and doctors, in a fashion hinting that the relation of cause and effect existed between both pairs:—

“As many laws and lawyers do express,

Nought but a kingdom’s ill-affectedness.

Even so those streets and houses do but show

Store of diseases where physicians flow.”

It was an old story this linking of the practitioners of law and medicine in one yoke of abuse. The reason given for both categories in early satire is sufficiently curious. It was because they took fees! Walter Map declared the Cistercian creed to be that no man could serve God without mammon. Ancient satire equally objected to the service of man, either legally or medically, under these conditions. “The Romaunt of the Rose” has the traditional refrain of other strictures in verse, when it declares that

“Physiciens and advocates,

Gon right by the same yates,yates, gates

They selle hir science for winning.winning, gain

- ···

For they nil in no maner greeno kind of good will

Do right nought for charitee.”

The same idea, precisely, finds voice in the poem attributed to Walter Map, wherein the doctor and the lawyer come together under the lash, because no hope can be based upon either of them unless there be money in the case. “But if the marvellous man see coin, the very worst disease is quite curable, the very falsest cause just, praiseworthy, pious, true, and pleasing to God.” Perhaps these ancient sarcasms were keener on the leech than the lawyer. “The Romaunt of the Rose” goes so far as to say that if the physicians had their way of it,

“Everiche man shulde be seke,

And though they dye, they set not a leke

After: whan they the gold have take

Ful litel care for hem they make.

They wolde that fourty were seke at onis!

Ye, two hundred in flesh and bonis!

And yit two thousand as I gesse

For to encresen her richesse.”

No doubt the men of medicine would have been much more vulnerable on another line, for it was no satirist but a learned medical professor, Arnauld de Villeneuve, who, in the beginning of the fourteenth century, advised his students as follows:—“The seventh precaution,” said he, “is of a general application. Suppose that you cannot understand the case of your patient, say to him with assurance that he hath an obstruction of the liver.” No legal professor surely was ever guilty of the indiscretion of saying such a thing as this!

The ineradicable public prejudice against legal charges as flagrantly exorbitant is only a modified form of an older idea exemplified above that lawyers should have no fees at all. And as to this day the plain man has never fully reconciled himself to the doctrine that the lawyer is only an agent, and not called upon to sit in the first instance in judgment on his client, so in the past the professional defence of a criminal appeared a very venal transaction.

“Thow I have a man i-slawe,

And forfetyd the kynges lawe

I sal fyndyn a man of lawe

Wyl takyn myn peny and let me goo.”

How reprehensible a thing to take fees was long reckoned admits of curious illustration. “Before the end of the thirteenth century,” says that never-failing authority, Pollock and Maitland’s “History of English Law,” “there already exists a legal profession, a class of men who make money by representing litigants before the courts and by giving legal advice. The evolution of this class has been slow, for it has been withstood by certain ancient principles.” Amongst these retarding influences lay the half-religious scruple about the propriety of payment—men as usual swallowing the camel first and straining at the gnat afterwards. Of course the subject had to be illuminated by monkish tales and death-bed repentances. There was, according to the Carlisle friar who penned the “The Chronicle of Lanercost,”—writing under the year 1288,—a young clerk in the diocese of Glasgow, whose mind “was given rather to the court of the rich than to the cure of souls. He was called Adam Urri, and was laically learned in the laic laws, disregarding the commands of God against the Praecorialia [so in the printed text, but, query, Praetorialia?] of Ulpian. He used the statutes of the Emperor in litigating causes, for payment of money. But when he had grown old and famous in this his wickedness, and was striving by his astuteness to entangle the affairs of a poor little widow, the divine mercy laid hold on him, assailing his body with sudden infirmity, and bringing his mind to plead (enarraret) more for another life.” Condemning utterly the lawyer’s court, he turned over a new leaf, predicted the day of his own death, and died punctually conform to the prophecy, leaving an example unctuously used by the friar to teach future generations “how wide was the gulf betwixt the service of God and the vanity of this world.” We shall not be far wrong in regarding, as of more historic interest, the indication of the immorality of fees, and the important reference to Ulpian as an authority in the forum causidicorum of thirteenth century Scotland.

Amongst the amiable conceptions of the middle age was the notion that the Evil One often manifested a particular zeal against sin. He was regarded with a different eye from that with which we regard him, and he rewarded faith with actual appearances such as only spiritualists can now-a-days command. Some of them were not very engaging, however praiseworthy may have been their object and occasion. Simeon of Durham, an eminently respectable contemporary author, wrote of the death of King William Rufus in the year 1100 that the popular voice considered the wandering flight of Tyrell’s arrow a token of the “virtue and vengeance of God.” And he added that about that time the Devil had frequently shewn himself in the woods “and no wonder, because in those days law and justice were all but silent.” The logic of this because, not apparent on the surface, becomes less obscure when it is remembered that in the mediæval devil the character of Arch-Enemy is so much subordinated to that of Arch-Avenger.

The direct relation of not only the Saints but of the Deity itself to human affairs was a conception so clear to the mediæval mind that it saw nothing irreverent in a title deed being taken in the Supreme name, or in marshalling “Deus Omnipotens” at the head of the list of witnesses to a charter. This anthropomorphic practice gave occasion to one of the sharpest of Walter Map’s jokes against the Cistercians. Three abbots of that order petitioning on behalf of one of their number and his abbey for the restoration of certain lands by King Henry II. as having been injuriously taken away from the claimant’s abbey, represented to the King in his court that for God’s sake he ought to cause the lands to be restored and they assured him and gave him God himself as their guarantor (fidejussorem) that if he did, God would greatly increase his honour upon earth. King Henry found it difficult to resist the appeal thus made to him but called the Archdeacon Walter Map to advise. This he did well-knowing that this counsellor did not love the Cistercians, and that he might thus find a creditable way out of a tight corner. The Archdeacon was equal to the occasion. “My lord,” said he to the King, “they offer you a guarantor; you should hear their guarantor speak for himself.” “By the eyes of God,” replied Henry, “it is just and conform to reason that guarantors themselves should be heard upon the matter of their guarantee.” Then rising with a gentle smile (not a grin, expressly says Giraldus Cambrensis) the shrewd monarch retired leaving the disappointed abbots covered with confusion.

Of the many ties between literature and law, one, not by any means the least interesting on the list, is the quantity of legal citations, phrases, metaphors and analogies which got swept into the wide nets of the poets. Amongst such scraps there are few so successful and still fewer so pathetic as one in which a metrical historian, drawing near the close, both of his days and his chronicle, figured himself as summoned on short induciæ at the instance of Old Age to appear at a court to answer serious charges, where no help was for him save through grace and the Virgin as his advocate.

Elde me maistreis wyth hir brevis,elde, age

Ilke day me sare aggrevis,brevis, writ

Scho has me maid monitiouneilke, each

To se for a conclusiounequhilk, which

The quhilk behovis to be of det;of det, of right

Quhat term of tyme of that be set

I can wyt it be na way,wyt, know

Bot weill I wate on schort delay

At a court I mon appeire

Fell accusationis thare til here

Quhare na help thare is bot grace.bot, without

The maikless Madyn mon purchacemaikless, matchless

That help; and to sauff my statepurchace, procure

I haiff maid hir my advocate.sauff, save

Androw of Wyntoun’s verse it must be owned was verse on the plane of a notary public, and oft the common form of legal writ supplied sorrily enough the deficiencies of his imagination. But here for once the simple dignity of the thought bore him up and carried him through.

A VLSI Architecture for Video Object Motion Estimation using a Novel 2-D Hierarchical Mesh

This paper proposes a novel hierarchical mesh-based video object model and a motion estimation architecture that generates a content-based video object representation. The 2-D mesh-based video object is represented using two layers: an alpha plane and a texture. The alpha plane consists of two layers: (1) a mesh layer and (2) a binary layer that defines the object boundary. The texture defines the object’s colors. A new hierarchical adaptive structured mesh represents the mesh layer. The proposed mesh is a coarse-to-fine hierarchical 2-D mesh that is formed by recursive triangulation of the initial coarse mesh geometry. The proposed technique reduces the mesh code size and captures the mesh dynamics.

The proposed motion estimation architecture generates a progressive mesh code and the motion vectors of the mesh nodes. The performance analysis for the proposed video object representation and the proposed motion estimation architecture shows that they are suitable for very low bit rate online mobile applications and the motion estimation architecture can be used as a building block for MPEG-4 codec.

Wael Badawy “A VLSI Architecture for Video Object Motion Estimation using a Novel 2-D Hierarchical Mesh,” Journal of Systems Architecture, ISSN 1383 – 7621, invited

You are not running a business. You are copying grandma's hobby of making pies.

Like all grandmas, she had the hobby of making pies and we receive lots of them to make her happy. Like it or not, as grandkids, we are told to thank our grandma for the pie and tell her how wonderful is the pie, how we cannot resist finishing the last pie, which was the best. Then we ends up having more pies, although we did not like the pies till today.

Grandma is a very senior, (and I hate to say “old”) with very limited mobility and almost no eyesight. She will challenge her ability to make more pies and send them to her grandkids because she believes she makes them happier.

I was invited to the introduction of a new product with the business owner, and I was told that it is better product that best serve my health and my life.

I was given a bottle to try and I am just curious. I was told that it is a new product that is better than anything else for my health. I was intrigued and as I start to ask simple questions to find a reason to try the sample.

After asking few questions, I found a very strong resistance to answer these simple questions. Then, I was framed as a consultant who is looking for new clients. Then, I was told to not impose my service. The fact is I am not a consultant and I am not shopping for new clients. I wonder, if I should ask the business owner to simply search my name on google “Wael Badawy” to know who I am and what I do.

The product is introduced, as a combination of ingredients that I know, ingredients that I do not know, and ingredient that I may not heard about it.

This introduction triggered a flag, because I do not generally eat or drink what I do not know, in the absence of a strong motive, such as being ill.

THEN, the ingredients are very healthy and it has better fruits and vegetables that I do not know but I should consume for their valuable impact.

I am not sure what is missing here? But, my understanding is the consumers of organic products like to know everything about their food. They do not like the unknown chemicals that may impact their health. At this point, I saw the second flag, because I was judged again.

For me, rightly or wrongly, “organic” is good enough to justify its high price, but “organic” or natural ingredients that I do not know to be better for my health, is not true. Pure marijuana and marijuana’s leaves are organic and natural but they are dangerous and even though we need to know more details to understand its medicinal effect. If I consume it, I will be addicted and most likely, I will end up in Jail but I am consuming an organic natural plant!!!

THEN, the product’s presentation explained the principle of consuming the full fruit/vegetable in a juice, against extracts. In my mind, this principle is questionable with diverse arguments. As a matter of fact, having a full lime as a juice will change its flavor and texture with time because of oxidation, and it can turn to be poisoning or has a higher level of toxic. On the other hand, I cannot consume the whole orange or the whole banana. I have to peal it first!!!

– Anyway, I will pass on this argument because I am not the expert in food but I know what I eat.

At this point, I started to ask questions to better understand who is the business owner, what is the value of the product and what is the quality of the product in order to have a level of confidence to try the product.

I asked about the size of the business, to feel comfort that there are others who trust this product and buy it. I was looking for the customers’ WHY to compare it to mine, i.e. what are the reasons to buy this over-priced product. Oh, this product will cost 25x – 35x the price of a high quality 100% natural juice.

I asked about the plan to grow the business in the next three or five years. I asked about the vision of the owner to confirm the quality of the product, and there is someone stands behind the product. All what I received is “3 and 5 years are very long time”. In the absence of an answer, it demonstrates that there is no continuity and no guarantee to a quality control process. i.e. two samples of the product with the same ingredient, will have different taste.

I asked about the value of the product? The question aimed to help me to find my WHY, and I can try the sample. The articulated value is “You drink good natural stuff, so your body will perform better”. There is no confirmation or reference other than the business owner has issues and it was solved by personally drinking this combination. There was no testimonial and no confirmation of the business owner story. So, I attempted to clarify and I asked, does it help with a diet plan? or release weight? or having high energy? etc. The value was articulated as you eat better ingredients, you will be healthier and you feel good, with a proof.

I do not eat pizza and burger everyday and I eat apple and banana everyday. As it was said “One apple a day, keeps the doctor away!!!”

The articulated value is very general and I can have a blinder. I will use a mix of fruits and vegetables. AND, WOW, the juice will have the same value.

The answer continues to be “the ingredients used are planted by the owner in business owner’s garden and then picked and prepared to make the product!!!”

I asked about the science or the research behind this drink. The answer is that the business owner has researched each of the known and unknown ingredients. But, the business owner has two degrees (none of them are related to food, or health or technology or medicine). Yes, everyone may be impressed of these two degrees that have no relation to the business.

Moreover, the business owner has no passion to either degree and do not work with these degrees but the business owner offers this product to serve and help others.

The product looks professional with an expiry date to expire in two days!!! The product comes in a quantity of 1, 4 and 8 bottles. I do not know the reason that of the expiry date given that there is no research or science behind the product to determine the impact of the three days instead of two. I wonder If someone orders a pack of eight bottles, will he/her consome them all in two days. What about the logistics of producing, distributing and consuming a product that has to be kept cold (I assume) in two days?

It translates to a very limited number of customers with limited quantity orders, within a very small geographical area. So, the production, distribution and consumption in two days!!!.

I have to say that this is not a business, this is a grandma hobby to make pies, as:

1- The pies are initially FREE, till she asks for a favor in return, which will be fairly pricy.

2- The ingredients are from grandma apple tree in the backyard – Oh, by the way, the apple tree is very natural and very organic, because grandma is a senior and can not take care of the apple tree and no one fertilizes the tree.

3- Grandma believes that she makes her family happier by offering more pies. She consumes her effort, while her grandkids do not prefer to eat the pies, or do not eat them at all.

4- Grandma’s pies have to be eaten hot, and within one or two days.

5- No one knows the secret ingredient of the pies, even grandma herself does not.

6- Grandma pies taste differs from time to time. It is a function of the mood and the time in the oven, but grandma does not read the time.

7- Grandma serves only her family and close friends, which is a very limited consumer base.

The whole time, I was simply looking for a reason to try a sample of a new product. I may feel lucky to put my hand on a free sample of this product. I was trying to find a reason for myself. I know grandma, but I do not know the business owner. So please stop copying grandma hobby making pies and focus on building a business.

Note from the author:

This is a true story and I held the name of the product and business confidential because I have the care and passion to every small business and entrepreneur in our community. I strongly believe that the message within this post will help everyone in their business, So please let me know your thoughts below.

I declare that I owe the business owner the price of the sample because I did not feel comfort to drink it, which is my fault AND now the sample expired!!!

Devices of the Sixteenth Century Debtors.

By James C. Macdonald, f.s.a., Scot.

IN the year 1531, a certain John Scott, residenter in the good town of Edinburgh, was financially in a condition of chronic decrepitude. His household goods were rapidly going to the hammer, and one creditor, bolder than his fellows, decided to attack the impecunious personality of the common debtor. Writs from court and messengers of the law were severally set in motion; and on the earliest possible day one of those myrmidons served upon the debtor personally, a writ bearing the terrible title of “Letters of IV Forms.” The “coinless” John was therein warned that if he failed forthwith to pay or satisfy the lawful debt, for which decreet has gone out, he would (unless he went to prison in a peaceful way) be declared a rebel against the King’s Majesty.

Now John reasoned with himself that payment he could not make; outlawry he rather feared; and squalor carceris he could not endure. What was to be done? He had heard of the horns of the Hebrew altars: how that personal safety resulted from any manual attachment thereto. Was there some such boon in bonny Scotland? There was Holyrood, with its sanctified abbey. It was near; any port in such a storm. Down the Canongate, and straight to the sanctuary he ran—all to the manifest loss, injury, and damage of his creditors who followed, having got wind of this unique hegira from the red-nosed city guard. In vain the creditors pleaded; equally in vain were their threats. The canny Scot was warranted safe and skaithless against “all mortal.”

Annoyed at his debtor’s immunity from arrest, chagrined that any money John possessed had now been further dissipated in the Abbey admission dues to its protection giving portals—each creditor turned sadly to his “buiks of Compts” and superscribed over against John Scott’s name the expressive legend “bad debt.” And this John Scott became the forerunner, de facto, of a long line of “distressed” persons. Nay more, he secured an immortality as lasting as that of the sovereign whose solemnly sounding “Letters of IV Forms,” he spurned and left unanswered.

A generation later, and another new way of paying old debts is placed on record. To balance international honours it is of Anglican origin. Scoggan, the jester of the Elizabethan court, falls into financial distress. He borrows £500 from the Queen—mirabile dictu. Only a fool would have tried such a thing. It was put down as a “short loan,” but it soon became clear to the royal lender that its longevity would outlast her reign. To all demands the clownish borrower smilingly cried “long live the queen,” until at last his existence as court fool was in danger of being ended. But he would rather die than be evicted; and die he did. He became, theatrically speaking, defunct.

The late Scoggan was accordingly borne, to solemn music, past the royal garden; and the queen, seeing the mournful show—and knowing nought of its hollowness—asked whose it was. “Scoggan, Your Majesty,” was the reply. “Poor fellow,” she exclaimed, “the £500 he owed me I now freely forgive.” Whereupon the “defunct” sat up and declared that the royal generosity had given him a new lease of life.

“Thou rogue,” said the queen, “thou art more rogue than fool. Thou hast improved upon the plan of that John Scott, who, in the reign of my late cousin of Scotland, as Sir James Melvil tells me, got rid of the oldest debt and the longest loan.”

Laws Relating to the Gipsies.

By William E. A. Axon, f.r.s.l.

EARLY in the fifteenth century the gipsies made their appearance in Europe, and as strangers were not favourably regarded in those days the advent of these dark-skinned people, speaking a language of their own, dressing in a picturesque, but uncommon costume, and having their own rulers, and their own code of morals, and owning no allegiance to the laws of the land in which they sojourned, naturally attracted attention. At first some credence was given to their high-sounding pretensions, and the dukes, counts, and lords of Lesser Egypt received safe conducts and protection under the idea that they were engaged in religious pilgrimages. But the seal of the Emperor Sigismund would not protect them when the term of their pretended pilgrimage had expired, nor would the manners and customs of the gipsies substantiate any special claim to sanctity or religious fervour. Even the ages when the divorce was most marked between religion and morals would be staggered by the thefts, and worse outrages that were laid to their charge. Sigismund’s safe conducts are said to have been given not as Emperor, but as King of Hungary, and some of the gipsies were early employed as ironworkers in the realm of St. Stephen. In 1496 King Ladislaus gave a charter of protection to Thomas Polgar and his twenty five tents of gipsies because they had made musket bullets and other military stores for Bishop Sigismund at Fünfkirchen, but whatever consideration may have been shewn to them in the beginning, they speedily became objects of suspicion and dislike. There is not a country in Europe which has not legislated against them or endeavoured to exile them by administrative acts. Their expulsion from Spain was decreed in 1492, from France in 1562, and from various Italian states about the same time. Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands have also pronounced against them. The Diet of Augsburg in 1500, ordered their expulsion from Germany on the ground that they were spies of Turkey seeking to betray the Christians. This edict, though several times repeated, was non-effective.

In Hungary and Transylvania the authorities, hopeless of getting rid of the troublesome immigrants, took strong measures to bring them into line with the rest of the population. They were prohibited from using the Romany tongue, from retaining their gipsy surnames, from wandering about the country, from eating carrion, and from dealing in horses. Those fit for military service were to be taken into the army, and the rest were to live and dress and deport themselves in the same manner as the peasantry of the country. These regulations were not wholly effective, but the result of the efforts put forward by Maria Theresa, and her successors may be seen in the sedentary gipsies of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. At times they have been subjected to fierce persecution. In 1782, a dreadful accusation was brought against the Hungarian Romanis, when more than a hundred of them were accused of murder and cannibalism. The gang were said to have lived by highway robbery and murder, and to have cooked and eaten the bodies of their victims. At Frauenmark four women were beheaded, six men were hanged, two were broken on the wheel, and one was quartered alive. Altogether forty-five were executed and many more were imprisoned.

How much of this was suspicion substantiated by torture?

The gipsies came frequently in contact with the myrmidons of the law. “As soon as the officer seizes or forces away the culprit,” says Grellmann, “he is surrounded by a swarm of his comrades who take unspeakable pains to procure the release of the prisoner…. When it comes to the infliction of punishment, and the malefactor receives a good number of lashes well laid on, in the public market place, a universal lamentation commences among the vile crew; each stretches his throat to cry over the agony his dear associate is constrained to suffer. This is oftener the fate of the women than of the men; for as the maintenance of the family depends most upon them, they more frequently go out for plunder.” It is a noteworthy fact that Grellmann writing in 1783, has not a word of condemnation of the barbarous practice of flogging women.

In England as elsewhere the earliest of these romantic people were welcomed. In 1519, the Earl of Surrey entertained “Gypsions” at Tendring Hall, Suffolk, and gave them a safe-conduct. Still earlier in 1505, Anthony Gaginus, Earl of Little Egypt, had a letter of recommendation from James IV. of Scotland to the King of Denmark. James V. bestowed a charter upon James Faa, Lord and Earl of Little Egypt, by which he was privileged to execute justice upon his followers, much in the same way as the great barons were authorised to deal with their vassals. But they soon fell out of favour. In England, in the twenty-second year of Henry VIII. an act of parliament was passed which sets forth that there are certain outlandish people, who not profess any craft, or trade, whereby to maintain themselves, but go about in great numbers from place to place, using craft and subtlety to impose on people, making them believe that they understood the art of foretelling to men and women their good or ill fortune, by palmistry, whereby they frequently defraud people of their money, likewise are guilty of thefts and highway robberies; it is ordered that the said vagrants, commonly called Egyptians, in case they remain sixteen days in the kingdom, shall forfeit their goods and chattels to the king and be further liable to imprisonment. In 1537, Cromwell writes to the Lord President of the Marches of Wales, that the “Gipcyans” had promised to leave the kingdom in return for a general pardon for their previous offences, and exhorts the authorities to see that their deportation is effected. Many were sent to Norway, but the effort to extirpate them from the kingdom entirely failed. By an act of 1554, a penalty of £40 was to be inflicted upon any one knowingly importing them. Those gipsies, following “their old accustomed devlishe and noughty practises,” were to be treated as felons, but exception was made in favour of such as placed themselves in the service of some “honest and able inhabitant.” Many were executed, but the remnant survived and managed to hold a yearly meeting at the Peak Cavern or Kelbrook, near Blackheath. Still sterner was the law passed in 1562-3, which made it felony for any one born within the kingdom to join the fellowship of vagabonds calling themselves Egyptians. The previous acts had referred to the gipsies as an outlandish people, but now the native born were brought equally within the meshes of this sanguinary law. “Throughout the reign of Elizabeth,” as Borrow remarks, “there was a terrible persecution of the gipsy race; far less, however, on account of the crimes which were actually committed, than from a suspicion which was entertained that they harboured amidst their companies priests and emissaries of Rome.” The harrying of the missionary priests was in part dictated by the spirit of religious persecution, but in a still greater degree by the conviction that they were political emissaries, aiming at the subversion of the kingdom. The priests on the English mission had often to disguise themselves, and at times may have assumed the garb of wandering beggars, but they are not likely to have consorted with the Romans, whose language would be strange to them, and whose heathenish indifference to all dogmas, rites, and ceremonies, would be specially distasteful to zealous Catholics.

After “the spacious times” of great Elizabeth, the gipsies had a rest from special oppression, though they were of course still in jeopardy from the harsh laws as to vagrancy and those minor crimes, that are their characteristic failings. Romany girls were flogged for filching and fortune-telling, and Romany men were hanged for horse-stealing. They were looked upon with suspicion, and it was easy enough to raise prejudice against them. This was shewn in the notorious case of Elizabeth Canning. She was a girl of eighteen, employed as a domestic servant at Aldermanbury, and in 1753, disappeared for four weeks. On her return she asserted that she had been abducted and detained in a loft by gipsies, who gave her only bread and water to eat. Their aim she declared was to induce her to adopt an immoral life. Mrs. Wells, Mary Squires, George Squires, Virtue Hall, Fortune and Judith Natus, were arrested, and Wells and Squires were committed for trial. The proceedings, partly before Henry Fielding the novelist, were conducted with a laxity that seems now to be almost inconceivable. At the Old Bailey trial there was a remarkable conflict of evidence, but in the end Mrs. Wells was condemned to be burned in the hand, and Mary Squires to be hanged. Sir Christopher Gascoyne then Lord Mayor, was satisfied that there had been a miscarriage of justice and made enquiries, a respite was obtained and finally the law officers of the crown recommended the grant of a free pardon to Squires. The natural sequel was the prosecution of Canning for perjury. Fortune and Judith Natus now swore that they had slept each night in the loft where Canning declared she had been imprisoned, but it was very natural that people should ask why they had not given this important evidence at the previous trial. Mary Squires’ alibi was sworn to by thirty-eight witnesses who had seen her in Dorsetshire, and was, to some extent, invalidated by twenty-seven who swore that she was in Middlesex at the time. As she was too remarkable for her ugliness to be easily mistaken, there must have been some very “hard swearing.” Canning was convicted of perjury and transported, but the secret of her absence from New Year’s Day, 1553, until the 29th of January was never divulged. The case excited great interest, and the controversy divided the whole of the busy, idle “town,” into “Canningites” and “Gipsyites.”

The Tudor law (22 Henry VIII., c. 10) was repealed as “of excessive severity” in 1783 (23 George III., c. 51). The later legislation provides that persons wandering in the habit and form of Egyptians, and pretending to palmistry and fortune-telling, are to be deemed rogues and vagabonds (17 Geo. II., c. 5., 3 Geo. IV., c. xl.), and is liable to three months’ imprisonment (5 Geo. IV., c. lxxxiii.), and encamping on a turnpike road involved a penalty of forty shillings (3 Geo. IV., c. cxxvi., 5 and 6 William IV., c. 50). Some of the older enactments remained on the statute book, though not enforced, until the passing of the statute law Revision Act of 1863, by which many obsolete parliamentary enactments were swept away.

By the famous Poynings Act, English laws were declared applicable to Ireland. The gipsies were never common in the Isle of Saints, but by a special act they were, in 1634, declared to be rogues and vagabonds (10 and 11 Car. I., c. 4).

There are acts of the Scottish Parliament as early as 1449, directed against “sorners, overliers, and masterful beggars with horse, hounds, or other goods,” and that this would well describe the earlier gangs of gipsies is undeniable, but whether they were Romanis or Scots is a matter of controversy not easily decided in the absence of more definite evidence. A tradition of the Maclellans of Bombie says that the crest of the family was assumed on the slaying of the chief of a band of saracens or gipsies from Ireland. The conqueror received the barony of Bombie from the king as a reward. Having thus restored the fortunes of the family, the young laird of Bombie took for his crest a moor’s head with the motto “Think on.” If this legend was evidence, which it is not, there were gipsy marauders in Galloway in the middle of the fifteenth century. But in 1505, we have the entry of a gift by the King of Scotland of seven pounds to the “Egiptianis.” In the same year there is a letter already named, in which “Anthonius Gagino,” or Gawino, is recommended to the King of Denmark. In 1527, Eken Jacks, master of a band of gipsies, was made answerable for a robbery from a house at Aberdeen. In 1539, a similar charge was brought, but not proved, against certain friends and servants to “Earl George, callet of Egipt.” This chieftain was one of the celebrated Faa tribe. In 1540, George and John Faa were ordered by the bailies of Aberdeen to remove their company and goods from the town. This is the first action of a Scottish authority against the gipsies as gipsies. But, by a charter dated four days before the municipal decree, James V. confirms to “our lovit Johnne Faw, lord and erle of Little Egipt,” full power to execute justice over his tribe, some of whom had rebelled and forsaken his jurisdiction. In 1541, an act of the Lords of Council and Session decreed the banishment of the gipsies from the realm within thirty days, because of “the gret theftes and scathis” done by them. Some of them passed over the border, but not for long, and in 1553 the Faas again had a charter upholding their rights of lordship against Lalow and other rebels of their company. And in the next year their is a pardon to four Faas for the “slachter of umquhile Ninian Smaill.”

The gipsies had the favour of the Roslyn family, and it is said that Sir William Sinclair rescued “ane Egiptian” from the gibbet in the Burgh Muir, “ready to be strangled,” and that in gratitude the tribe used to go to Roslyn yearly and act several plays in May and June. In 1573, and again in 1576, the gipsies were ordered to leave the realm, but the decree was never put in force. When Lady Foulis was tried in 1590, one charge was that she had sent a servant to the gipsies for advice as to poison to be administered to “the young laird of Fowles and the young Lady Balnagoune.” When James VI. held a High Court of Justicary at Holyrood in 1587, for the reformation of enormities, the offenders to be dealt with included “the wicked and counterfeit thieves and limmers calling themselves Egyptians.”

There were several enactments of the Scottish Parliament in 1574, 1579, 1592, and 1597. These were all aimed at the nomadic habits of the race, but the settled gipsies were left unmolested. “Strong beggars and their children” were to be employed in common work for their whole life, and it is said that salt masters and coal masters thus made serfs of many. In 1603, there was a special “Act anent the Egiptians,” which declared it “lesome” for anyone to put to death any gipsy, man, woman, or child, remaining in the country after a certain date. Moses Faa appealed against it as a loyal subject, and found a security in David, Earl of Crawford. This was in 1609, but in 1611 four of the Faas were tried at Edinburgh under the acts against the gipsies, and were convicted and executed on the same day. Constables and justices of the peace were exhorted to put the law in force. Four gipsies, who could not find securities that they would leave the kingdom, were sentenced to be hanged in 1616, but were reprieved and probably released. In 1624, eight were executed on the Burgh Muir, but the women and children were simply exiled. In 1636, a number were condemned at Haddington, the men to be hanged and the women to be drowned. Women who had children were to be scourged and branded in the face. In the latter half of the seventeenth century many were sent to the plantations in Virginia, Barbadoes, and Jamaica.

Generally, however, the stringent laws were not stringently administered, and from fear or influence of some kind the gipsies often escaped.

The British gipsies in our own day find that whilst the law is dealt out to them with perfect impartiality, the social pressure is decidedly against them. At such watering-places as Brighton and Blackpool—to name two extremes—they tell fortunes as though there were no statutes in that case made and provided. But it is not easy for them to keep on the road. The time cannot be far off when they must live with the gaújos[11] as house-dweller or perish from the land.

Commonwealth Law and Lawyers.

Edward Peacock, f.s.a.

THE great Civil War as it is called, that is the struggle between Charles the First and his parliament, is memorable in many respects. No student of modern history can dispense with some knowledge of it, and the more the better, for it was the result of many things which had happened in the far distant past, and we may safely say that the great French Revolution, which produced some good, and such an incalculable amount of evil would have run a far different course to that which it did, had not the political ideals of the men who took part in that terrible conflict been deeply influenced by what had taken place in England a century and a half before.

As to the civil wars which had occurred in England in previous days, little need be said. They were either dynastic—the struggle of one man or one family against another—or they were religious revolts against the Tudors, by those who vainly endeavoured to re-establish the old order of things in opposition to the will of the reigning monarch and the political servants who supported the throne. The struggle between Charles and the Long Parliament was far different from this. That religion in some degree entered into the conflict which was raging in men’s mind long ere the storm burst it would be childish to deny, but it was not so much, except in the case of a very few fanatics, a conflict between different forms of faith as because a great number of the English gentry, and almost the whole of the mercantile class, which had then become a great power, felt that they had the best reasons for believing that it was the deliberate intention of the King and the desperate persons who advised him, to levy taxes without the consent of parliament. This may occasionally have been done in former reigns, but it is the opinion of most of those who have studied the subject in latter days, so far as we can see, without prejudice, that in every case it was illegal. Whether this be so or not, it must be remembered that times were in the days of Charles the First, far different from what his predecessors the Plantagenets and Tudors had known. A great middle class had arisen partly by the division of property consequent on the dispersion of the monastic lands, and partly also by the break up of the vast feudal estates, some of which had fallen into the hands of the Crown by confiscation, others been sold by their owners to pay for their own personal extravagence.

Though murmurs had existed for many years, it was not until the memorable ship-money tax was proposed that affairs became really grave. Had England been threatened by an invasion such as the Spanish Armada, there can be no doubt that a mere illegality in the mode of levying taxes to meet the emergency would have been regarded as of little account, but in the present case there was no overwhelming need, and it must be borne in mind that to add to the national irritation the two first Stuarts were almost uniformally unsuccessful in their foreign wars. It is to Attorney General Noy that we owe the arbitrary ship-money tax. He was a dull, dry, legal antiquary of considerable ability, whose works, such as his Treatise concerning Tenures and Estates; The Compleat Lawyer; The Rights of the Crown, and others of a like character, are yet worth poring over by studious persons. Such a man was well fitted for historical research, no one of his time could have edited and annotated The Year Books more efficiently, but he had no conception of the times in which he lived, the narrow legal lore which filled his mind produced sheer muddle-headedness, when called upon to confront an arbitrary king face to face with an indignant people. That there was less to be said against this form of royal taxation than any other that legal ingenuity could light upon must be admitted, but as events shewed the course he advised the king to take, was little short of madness. John Hampden, who represented one of the oldest and most highly respected races of the English gentry—nobles as they would be called in any land but our own—set the example of refusing to pay this unjust levy. The trial lasted upwards of three weeks, and the men accounted most learned in the law were employed in the case. Sir John Bankes, the owner of Corfe Castle, Sir Edward Littleton, and others were for the King. Oliver Saint John and Mr. Holborn were for Hampden. Concerning Holborn little seems to be known, but Saint John made for himself a great name. His speeches are marvellously learned, shewing an amount of reading which is simply wonderful when we call to mind that in those days all our national records were unprinted, and almost all of them without calendar or index of any sort. It must, however, be remembered that in those days lawyers of both branches of the profession were well acquainted not only with the language in which our records were written, but also with the hands employed at various periods, and the elaborate system of contraction used in representing the words.

A full report of this memorable trial is to be found in Rushworth’s Historical Collections, volume ii. parts 1 and 2. Carlyle in his Letters and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell, in the emphatic diction he was accustomed to use says that Saint John was “a dark, tough man of the toughness of leather,”[12] but he does not dwell on his great learning and general ability, as he ought to have done. That Saint John’s heart was in his work for his client we are well assured. That from a legal point of view, Hampden was his only client, we well know, but as a matter of fact, it is no exaggeration to say that he represented the people of England. The decision went in favour of the crown, which was from the first a foregone conclusion. It was a legal victory, but like many lesser victories won before and since success was the sure road to ruin. The sum contended for was absurdly small—twenty shillings only—but on that pound piece hung all our liberties; whether we were to continue a free people or whether we were to have our liberties filched away from us, as had already been the case in France and Spain. A sullen discontent brooded over the land, there was no rioting, but in hall and castle, country parsonage and bar-parlour, grave men were shaking their heads and asking what was to come next, all knew that a storm was brewing, the only question was when and where it would burst. Events changed rapidly, and Saint John though he took no very prominent part in the party struggles ere the war broke out, was undoubtedly the chief legal adviser of those who were in opposition to the faction which desired to make England a despotic monarchy. Such was the case during the war which ended in the tragic death of the king, and the establishment of a Republican form of government under the name of the Commonwealth. Saint John once again appears in a public manner which indicates that he was a brave man who had no more fear of the pistol and dagger of the assassin, than he had of the corrupt dealings of those who for a time, to their own imminent peril had misgoverned our country. This time we find him sent by the Commonwealth as ambassador to the seven United Provinces, then as now commonly called Holland, on account of the two provinces of north and south Holland, being by far the most influential states in that republic. The Dutch though republicans themselves, had during the latter part of our Civil War shewn sympathy with the cause of the Royalists. After the execution of the king, this feeling became naturally much intensified. On the other hand our newly established republic was for many reasons both of politics and religion very desirous of being on good terms with a sister commonwealth so very near at hand. To explain matters and perhaps to settle the heads of a definite treaty, the English government sent Isaac Doreslaus, or Doorslaer as their ambassador. He was by birth a Dutchman and a very learned lawyer. He had come to this country before, the war broke out in 1642. He was then made, probably through the influence of his friend Sir Henry Mildmay, “Advocate of the Army.”[13] His great knowledge of Civil Law, which had been much neglected in England in times subsequent to the Reformation, rendered him of great service in his new position of Judge Advocate of the Army. For the same reason he soon afterwards was created one of the judges of the Admiralty Court. He became especially hateful to the Royalists from his having assisted in preparing the charges against Charles the First. In May, 1649, he sailed for Holland as Envoy of the English government to the Hague. He had only spent a short time there, when, while at supper in the Witte Zwaan (White Swan) Inn, some five or six ruffians with their faces hidden by masks, rushed into the room where he, in company with eleven other guests were sitting. Two of these wretches made a murderous attack on a Dutch gentleman of the company, mistaking him for Dorislaus. Finding out their error they set upon the Envoy and slew him with many wounds, crying out as they did so, “Thus dies one of the King’s judges.” The leader of this execrable gang was Col. Walter Whitford, son of Walter Whitford, D.D. The murderer received a pension for this “generous action”[14] after the Restoration.

The English Parliament gave their faithful servant a magnificent funeral in Westminster Abbey, June 14, 1649, but when Charles the Second ascended the throne, his body was disturbed. His dust rests along with that of Admiral Blake and other patriots in a pit somewhere in Saint Margaret’s churchyard.[15] Dorislaus, though a foreigner, ought to rank among our great English lawyers, for his services were devoted entirely to his adopted country. Whatever our opinions may be as to those differences which were the forerunners of so much bloodshed and crime, we must bear in mind that many of the foremost men on both sides were actuated by the highest principles of honour. The study of Canon Law had been prohibited in the preceding century, and the Civil Law with which it has so intimate a connection, though not made contraband, was so much discouraged that it is no exaggeration to say that the knowledge of it was confined to a very few. Selden, whose wide grasp of mind took in almost every branch of learning as it was known in his day, is the only English lawyer we can think of who had mastered these two vast subjects. This is the more remarkable as he was of humble parentage; the son of a wandering minstrel it is said, but from the first his passion for learning overmastered all difficulties. It must, however, be borne in mind that according to the custom of those times when his abilities became known, he met with more than one generous patron.

We must for a moment return to Saint John who was selected in 1652, to represent his country in Holland. There was not, as there is now a trained body of men devoted to the diplomatic service. The reasons why Saint John was chosen for this important office are not clear. He was a great and widely read lawyer, who we apprehend was trusted with this difficult mission, not only because the government were assured of his probity, but because the relations between Holland and this country depended on many subtile antiquarian details which a mere student of the laws as they were then, would have been unable to unravel. The basis of the sea codes by which the various nations of Christendom professed to be ruled, was the Laws of Oleron (Leges Uliarences). They were promulgated by Richard the First of England, on an island in the Bay of Acquitaine. How far they were ever suited for their purpose may be questioned, but it is certain that as centuries rolled on, they had though often quoted, ceased to have any restraining power, and as a consequence Spain, England, Holland, and other powers were guilty of constant acts of what we should now call piracy. A lasting treaty with Holland, could Saint John achieve it, would have been of immense advantage, but the Dutch were in no mood for an alliance on equal terms. It was a brave thing for Saint John to undertake so arduous a mission, for he not only run the risk of ignominous failure, but also was in no little danger from the savage desperadoes who thought they did the cause of their exiled master service by murdering the agents of the English government. When Saint John arrived at the Hague he was put off by slow and evasive answers, which soon shewed to him not only that his own time was being wasted, but what was to him of far more account, the honour of his country was being played with. He gave a proud, short, emphatic reply to the Dutch sophistries, and at once returned home again, to cause the celebrated Navigation Act to be passed, forbidding any goods to be imported into England, except in English ships, or in the ships of the country where the articles were produced. This was well-nigh ruin to the trade of the Dutch, who were then the great carriers of the world.

In no sketch however brief of the lawyers of this disturbed time, can the name of William Prynne be entirely passed over, and yet it is not as a lawyer that his name has become memorable. Had he been a mere barrister at law he would long since have been forgotten, but he was an enthusiastic puritan of the presbyterian order, and a no less enthusiastic antiquary. He had probably read as many old records as Saint John or Selden, but had by no means their faculty of turning them to good account. He first comes prominently before us as attacking the amusements of the court, especially theatrical entertainments. For this he was proceeded against in the Star Chamber, sentenced to pay five thousand pounds and have his ears cut off; for an attack on episcopacy he was fined another five thousand pounds and sentenced once more to have his ears cut off. He afterwards bore a prominent part in the trial of Archbishop Laud. All along he continued to pour forth a deluge of pamphlets. He attacked Cromwell with such boldness, that the Protector felt called upon to imprison him in Dunster Castle, where however, his confinement was of a most easy character. He is said while there to have amused himself by arranging the Lutterell Charters, for which that noble home is famous. He took the side of Charles the Second at the Restoration, and as a reward was made keeper of the records in the Tower, a post for which he was peculiarly well fitted.

There is probably nothing which distinguishes the periods of the Commonwealth and the Protectorate more markedly from other times of successful insurrection, than the very slight alteration which the new powers introduced into the laws of England. The monarchy, it is true, was swept away, but the judges went on circuit; the courts of Chancery and common-law sat as usual, the Lords of Manors held their courts, and the justices of peace discharged their various functions as if they had been the times of profoundest peace. No confiscations took place, as had been the case in the reign of Henry the Eighth and his successor, except in cases where the owners had been engaged in what the state regarded as rebellion, and even with regard to those who had fought in what is known as the first war, almost everyone was let off by a heavy fine. A list of these sufferers may be seen in A Catalogue of the lords Knights and Gentlemen that have compounded for their Estates (London Printed for Thomas Dring at the Signe of the George in Fleet Street, neare Clifford’s Inne, 1655.) The book is imperfect and very inaccurate. This is not of much consequence however, as the documents from which it is compiled known as The Royalist Composition Papers, are preserved in the record office, and are open to all enquirers. Those who madly engaged in what is known as the second war, had their estates confiscated by three acts of parliament of the years 1651 and 1652. These were reprinted and indexed for the Index Society in 1879. These latter had their estates given back to themselves or their heirs on the Restoration. It does not seem that those who were fined, except in a very few cases had any return made to them. There have been few civil wars ancient or modern wherein the unsuccessful have been so tenderly treated. Yet sufferings of the poorer classes among the Royalists must have been very great. Next to the arbitrary conduct of the King and those immediately about his person, was the provocation which the Parliamentarians thought that the established church had given, firstly because many of the bishops and clergy maintained an extreme theory of the Divine Right of Kings, which is said first to have been taught in this country by Archbishop Cranmer. If this opinion were really accepted as more than a mere figure of flattering oratory, it made those who complied with it mere slaves to the sovereign, however tyrannical or wicked he might prove himself. The second ground of resentment was that they thought Archbishop Laud and many of the bishops and clergy, concealed Roman Catholics, “disguised Papists,” as the common expression ran. We do not believe this charge with regard to Laud or most of the others so rashly accused. We are quite sure it was not so if their writings are to be taken as a test of their feelings. Whatever may have been the truth, there is no doubt that even the more tolerant of what may be called the low-church party feared the worst. As early as 11th February, 1629, Oliver Cromwell, who was then member for Huntingdon, made a speech in which he said, “He had heard by relation from one Dr. Beard … that Dr. Alablaster had preached flat Popery at Paul’s Cross, and that the Bishop of Winchester (Dr. Neale), had commanded him as his Diocesan, he should preach nothing to the contrary.”[16] So inflamed, however, were men’s minds that as soon as the Parliamentary party was strong enough, Laud was indicted for high treason and beheaded.

One of the first works of the Parliament when strong enough, was to abolish the Book of Common Prayer, and put a new compilation called the Directory in its place. The use of the Prayer Book was forbidden not only in public offices of religion, but in private houses also. For the first offence five pounds was to be levied, for the second ten, and for the third the delinquent was to suffer one year’s imprisonment.[17] Whether this stringent law was rigorously inforced we cannot tell. Probably in many cases the local justices would be far more lenient to the clergy who were their neighbours, that would be the legislators at Westminster, whose passions were fanned by listening to the popular preachers. Not content with interfering with the service-book, various acts were passed relating to “Scandalous, Ignorant, and Insufficient ministers.” That the commissioners who put these acts in force removed some evil persons we do not doubt, but if John Walker’s attempt towards recovering an account of the number and sufferings of the Clergy of the Church of England, who were sequestered … in the Grand Rebellion, be not very grossly exaggerated, which we see no reason, to believe, many innocent persons must have had very hard treatment.

The marriage laws of England were in a vague and unsatisfactory state from the reign of Edward the Sixth, until the Commonwealth time. An attempt was made in 1653 to alter them. Banns were to be published either at Church or in the nearest market town on three market days, after this the marriage was to take place before a justice of peace. Many entries of marriages of this kind are to be found in our parochial registers. English was made the language of the law in 1650, but Latin was restored to the place of honour it had so long held, when the Restoration took place.

You are not running a business. You are copying a grandma's hobby of making pies.

Like any grandma, she had the hobby of making pies and we use to receive lots and lots of pies to make her happy.

Like or not, grand kids are told to always thank grandma for the pie and tell her how wonderful is the pie, how they can not resist the last pie which was the best. It ends up of having more pies, although they never liked the pies till today.

Grandma is a very senior, (and I hate to say old) with very limited mobility and very bad or no eyesight will challenge her ability to make more pies and send them to her grand kids as she believes she makes them happier.

I was invited to an introduction to a new product with the business owner and I was told that is better for my health and my life. I was given a bottle to try and I just curious. I was told that it is a new product that is better than anything else for my health. I was intrigued and as I start to ask simple questions to find a reason to try the sample.

I found a very strong resistance to answer simple questions. I was framed as a consultant or to be in the business of helping others. I was told to not impose my service. I am not consult and I am not in the business find other businesses to offer them service. I think they should simply search my name on google “Wael Badawy” and they will know who I and what I am not doing.

The product was introduced as a mix of some ingredient that I know and others that I do not know and I may not heard about it. – It triggers a flag to me because I am not in a position to eat or drink what I do not know in the absence of a strong motive. I am also framed that there are fruits and vegetable that I should be taken but I do not them, I am not sure what I am missing !!!

I predict that the consumer of these products are the type of individuals who are using organic products because they like to know everything about their food and they do not like the chemical that they do not know and may impact their health. I saw the second flag, because I was judged again.

I want to say that “organic” is good to justify its high price, but “organic” or natural ingredient that I do not know is better, is not true. Pure marijuana or marijuana’ s leaves are danger plant and even though we need to know more details to understand its medicinal effect. If I consume it, I will be addicted and I may end up in Jail because I am using an organic natural plant !!!

Then the presentation went to explain that principle of consume the whole fruit/vegetable as a juice, against extracts. In mind, it is questionable with many diverse arguments. As a matter of fact, having a full lime as a juice will change its flavour and texture with time because of oxidation, and it can turn to be poisoning or has higher toxic. I can not consume the orange or the banana as a whole, I have to peal it first !!! – Anyway, I will pass on this argument because I am not the expert but I know when i eat.

Then I started to ask questions to better understand who is the owner, what is the business value and what is the quality of the product in order to give me a level of confidence to try the product.

I asked about the size of the business, to feel comfort that there are others trust and use this product. I was looking to understand their WHY, or what are the reasons to buy this over priced product.

I asked about the growth plan in the next three or five years. I asked about the vision of the owner to simple get a confirmation and make sense of the quality of the product and there is someone stands behind it. All what I received is “3 and 5 years are very long time”. In the absence of an answer, it demonstrates that there is no continuity no guarantee to a quality control or that the same product at different time will have the same ingredient and taste the same.

I asked about the value of the product is to try to find my WHY, to tryout the sample. The articulated value is “You drink good natural stuff, so your body will perform better”. I asked, does it help with a diet plan, or release weight, or having high energy, etc. The value was articulated well, you eat better ingredient, you be healthier and you feel good. First of all, I do not eat pizza and burger all days and I eat apple and banana every day. “One apple a day, keeps the doctor away!!!” The articulated value is very general and I can have a strong blinder and I use organic mix of fruits and vegetables. AND, WOW, the mix will have similar value. The answers continues to be “the ingredients used are planted by the owner in business owner garden!!!”

I asked about the science or the research behind this drink. The answer that the business owner has researched each one of these ingredient. The business owner has two degrees (none related to food, or health or technology or medicine) and everyone is impressed of these two degrees with no relation to the business. Moreover, the business owner has no passion to either degree and do not work in these areas and offers this product to serve and help others.

The product looks very professional with an expiry date of two days!!! The product comes in a quantity of 1, 4 and 8. I also noted that the bottle has an expiry date within two days. I do not know the reason that of the expiry date given that there is no research or science behind the product. I wondered If someone want to order a pack of eight bottles, will he/her use them all in two days. what about the logistics of producing, distributing and consuming, a product that has to be kept cold (I assume) within two days. It mean that a very limited number of customers with limited quantity orders, within a very small geographical area. So the production, distribution and consumption in two days !!!.

This is not a business, this is a grandma hobby to make pies, it is:

1- The pies are initially FREE till she as for a favour in return, which will be fairly pricy.

2- The ingredient is from grandma apply tree in the back yard – Oh, by the way, it is natural and very organic because grandma is not in heath conditions to take care of the tree or even fertilize the tree.

3- Grandma believes she makes her grand kids happier by offering more pie and she consumes her effort, while the grandkids do not prefer to eat the pies, or do not eat them at all.

4- Grandma pies have to be eaten hot, and within one or two days.

5- No one knows grandma secret ingredient, even grandmas

6- Grandma pies differ from time to time, based on the mood and the time in the oven, grandma can not read the time.

7- Grandma serves only her family and friends which has a very limited consumer base.

The whole time, I was simply looking for a reason to try a sample of a new product. I may feel lucky to put my hand on a free sample of this product and I was trying to find the reason for myself. BUT, I know grandma but I do not know you. So please stop copying grandma hobby to make pies and focus on building a business.

Note from the author:

This is a true story and I held the name of the product and business because I have the care and passion to every small business and entrepreneur in our community. I strongly believe that the message will help everyone in their business, So please let me know you thought below.

I also say that I owe the business owner the price of the sample because I did not feel comfort to drink it which is my fault and the sample passed the expiry date!!!

The Little Inns of Court.

THE origin of the decadent institutions located in certain grim and dreary-looking piles of building dotting the district of the Inns of Court proper, and known as the little Inns of Court, is involved in considerable obscurity. They appear to have originally held a similar position to the great seats of legal education as the halls of Oxford and Cambridge do to the Universities. But at the present time their relation to the Inns of Court proper is not very clear, and the uses they serve, otherwise than as residential chambers, are just as hard to discover. This state of mistiness concerning them has existed so long that no one now seems to know anything about them, and the evidence taken more than forty years ago by a Royal Commission did so little to clear away the dust and cobwebs hanging about them that they still remain, in the words of Lord Dundreary, “things that no fellow can understand.”

Lyon’s Inn has since that time been swept

away to make room for the new Courts of Law, without any person evincing the smallest interest in its fate. Concerning this institution all that could be learned by the Royal Commission was contained in the evidence of Timothy Tyrrell, who “believed” that it consisted of members or “ancients,” he could not say which; he believed the terms were synonymous. There were then only himself and one other, and within his recollection there had never been more than five, and they had nothing to do beyond receiving the rents of the chambers. There were no students, and the only payment made on account of legal instruction was a sum of £7 13s. 4d. paid to the society of the Inner Temple for a reader; but there had been no reader since 1832. He had heard his father say that the reader “burlesqued the things so greatly” that the ancients were disgusted, and would not have another. There was a hall, but it was used only by a debating society; and there was a kitchen attached to it, but he had never heard of a library.

New Inn appears to have been somewhat more alive than Lyon’s, though it does not seem to have done any more to advance the cause of legal education. The property is held under the

by a lease of three hundred years from 1744, at a rent of four pounds a year. Among the stipulations of the lease is one allowing the lessors to hold lectures in the hall, but none had been held since 1846, in consequence, it was believed, of the Middle Temple ceasing to send a reader. The lectures never numbered more than five or six in a year; and there is now no provision of any kind for legal education. Samuel Brown Jackson, who represented the inn before the Royal Commission, said he knew nothing concerning any ancient deeds or documents that would throw any light on the original constitution and functions of the body. If any there were, he “supposed” they were in the custody of the treasurer. The only source of income was the rents of chambers, which then amounted to between eighteen and nineteen hundred pounds a year; and the ancients have no duties beyond the administration of the funds.

Concerning the origin of Clement’s Inn, Thomas Gregory, the steward of the society, was unable to afford full information, but he had seen papers dating back to 1677, when there was a conveyance by Lord Clare to one Killett, followed by a Chancery suit between the latter and the principal and ancients of the society, which resulted in a decree under which the property so conveyed became vested in the inn. Some of the papers relating to the inn had been lost by fire, and “some of them,” said the witness, “we can’t read.” The inn, he believed, was formerly a monastery, and took its name from St. Clement. It had once been in connection with the Inner Temple, but he could find no papers showing what were the relations between the two societies, “except,” he added, “that a reader comes once a term, but that was dropped for twenty years—I think till about two or three years ago, and then we applied to them ourselves, and they knew nothing at all about it; the under-treasurer said he did not know anything about the reader, and had forgotten all about it.” It was the custom for the Inner Temple to submit three names to the ancients; and, said the witness, “we chose one; but then they said that the gentleman was out of town, or away, and that there was no time to appoint another.” But no great loss seems to have resulted thereby to the cause of legal education, for it appears that all a reader had ever done was to explain some recent Act of Parliament to the ancients and commoners, there being no students. The inn had no library and no chapel, but as a substitute for the latter had three pews in the neighbouring church of St. Clement, and also a vault, in which, said the witness, “the principals or ancients may be buried if they wish it.”

Some remarkable evidence was given concerning Staples Inn, and the more remarkable for being given by Edward Rowland Pickering, the author of a book on the subject, which publication one of the Commissioners had before him while the witness was under examination. “You state here,” said the Commissioner, “that in the reign of Henry V., or before, the society probably became an Inn of Chancery, and that it is a society still possessing the manuscripts of its orders and constitutions.” “I am afraid,” replied the witness, “that the manuscript is lost. The principal has a set of chambers which were burnt down, and his servant and two children were burnt to death, seventy years ago; and I rather think that these manuscripts might be lost.” Where the learned historian of the inn had obtained the materials for that work is a question which he does not appear to have been in a position to answer; for when asked whether he knew of any trace of a connection between the society and an Inn of Court, he replied, “Certainly, I should say not. It is sixty years since I was there, boy and all.” A very strange answer considering the statement in his book. During the sixty years he had been connected or acquainted with the society, he had never heard of the existence of a reader, or of any association of the inn with legal education or legal pursuits. The only connection claimed for the inn by the principal, Andrew Snape Thorndike, was that, when a serjeant was called from Gray’s Inn, that society invited the members of Staples Inn to breakfast. There is a singular provision respecting the tenure of chambers in this inn by the ancients. “A person,” said this witness, “holds them for his own life, and though he may be seventy years of age, if he can come into the hall, he may surrender them to a very young man, and if that young man should live he may surrender them again at the same age.” If a surrender is not made, the chambers revert to the society.